How the north was won…Bendigo wins the rail line battle

18 October, 2022

This is part two of a presentation delivered by CMRT researcher David Tuck with Lee Fenton for CMRT’s gig at the 2022 Words in Winter literary festival in Maryborough. In part one, David described coach travel before the arrival of trains. In the second installment, David profiles the fate of the Bendigo line, along with plans for a wider Victorian rail network.

It’s not surprising that in the mid-1850s, and for the next 70 years, every community wanted access to a railway. Let’s consider what is involved in building a railway line. First, you need to demonstrate a need for the line, including financial return. Then you have to decide on a route, get quotes for its construction, and persuade a parliament to allocate the funding.

How were the routes to be prioritised? The top priority was to build them to the major population centres: Geelong and the goldfield towns of Ballarat and Bendigo, and of course the suburbs of Melbourne. The route to these towns needed to service as many other communities as possible, and was subject to intense debate. Railway Advancement Leagues sprung up in many towns. The turn of history that the Bendigo line went via Castlemaine was by no means guaranteed.

This line to Bendigo had another important agenda. In colonial times, Victoria and News South Wales were often in competition with each other: one could prosper at the other’s expense. The Bendigo line was conceived as a line to Echuca that would lower the cost of transport and draw trade from the Riverina to Melbourne rather than to Sydney.

The Melbourne, Mount Alexander & Murray River Railway Company was set up in 1853 to build that line, but, under immense financial pressure, it was sold to the government within several years, having only reached Footscray from Williamstown. The railway line eventually reached Castlemaine and Bendigo in 1862, and Echuca by 1864.

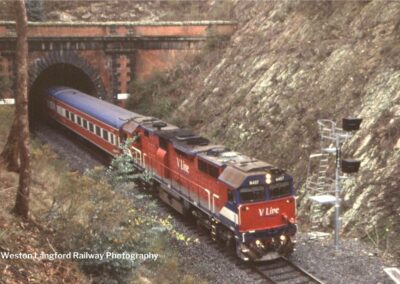

These new lines to the goldfields were absolute showpieces: according to one expert, built to the highest engineering standards, unrivalled by any lines built in Australia thereafter. The breath-taking viaducts at Malmsbury (see feature image above) and Taradale support this claim, as is the less obvious long tunnel at Elphinstone (see image gallery below).

The 1860s and 1870s were decades of financial stagnation in Victoria, but new lines were urgently needed – on this there was little disagreement.

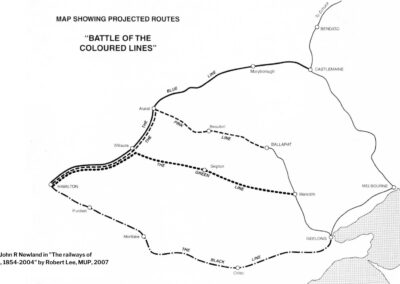

The map by John Newland shows the main contenders for railway lines in 1870: four different routes to Hamilton as proposed in 1870 by Victorian Railways Chief Engineer, Thomas Higinbotham. All these lines were eventually built, albeit in modified form, as discussed in Robert Lee’s wonderful history, ‘The railways of Victoria’.

Dubbed the “Battle of the Coloured Lines”, the black, green, pink and blue lines show proposed routes to the central highlands and the western district (see image gallery below). (Blue is the local favourite!)

What is not shown on this map is the line from Ballarat to Maryborough, the construction of which was approved by parliament at the same time as our line, in late 1871. Two lines were being constructed towards Maryborough at the same time.

Ours was to be the first light line built in Victoria. Construction costs were set at an ambitious £5,000 per mile, roughly half the amount spent on the Main Line to Echuca. To achieve this, two possibilities were hotly debated, and the engineers disliked both: either narrow gauge or light gauge. When the tenders for narrow gauge (3’6”) proved to offer little cost saving compared to broad gauge (5’3”), attention switched to the light gauge option.

Light gauge meant, quite literally, using steel rails that were lighter than the standard: just 50 lbs per yard compared to up to 80 las. Although initially cheaper, this dubious economy would lead to higher running costs due to slower speeds by lighter trains.

Part three in this series will describe the construction of our local line and the prevailing economics.